|

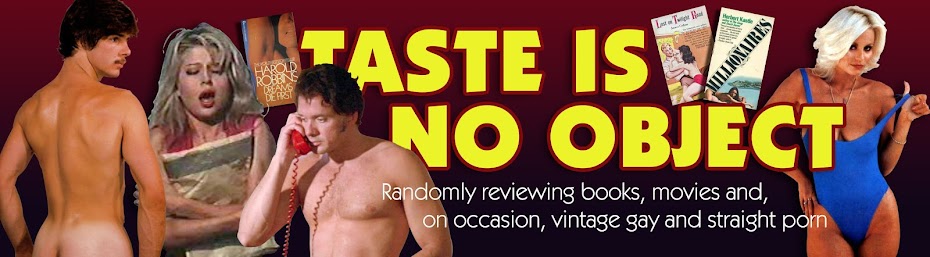

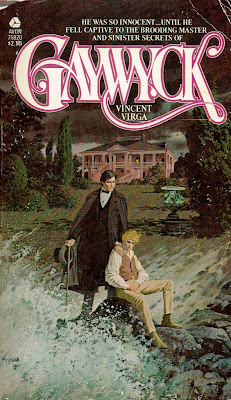

The original cover of Lost on Twilight

Road is as misleading as it is tacky. |

I really intended this to be my second Pride Month post, but work, life and shit got in the way of me meeting my self-imposed deadline. But then, shouldn't Pride be celebrated all year long?

With that in mind, let’s get back in the closet! Let’s get LOST ON TWILIGHT ROAD.

I first learned of this 1964 novel, written by the late Joseph Hansen under the pseudonym James Colton, in the early 2000s when I read about it in Susan Stryker’s Queer Pulp: Perverted Passions from the Golden Age of the Paperback. While there were many titles discussed in Queer Pulp that piqued my interest, only Styker’s overview of Lost on Twilight Road, which she described as a “white trash epic,” sparked an obsession. I didn’t just want to read Lost on Twilight Road, I had to.

Of course, Twilight Road was long out of print and difficult to find. I discovered a copy on Alibris shortly after reading about it in Queer Pulp but was put off by the nearly $60 price tag. Turned out, $60 was a bargain. The next time I found the book for sale online, the price was over $200, and it just went up from there. I gave up when I saw it listed for over $450 on Amazon. But then, in the mid-2010s, it popped up on eBay with a relatively modest opening bid. The price didn’t stay modest for long, but I managed to stay one step ahead of the escalating bids, until I finally got the news I’d hoped for: I had won Lost on Twilight Road! I won’t reveal how much I paid for it, but it was worth every penny.

The protagonist of Lost on Twilight Road is Lonny Harms, who, contrary to what the cover illustration would have readers believe, is a cute, blond 16-year-old boy, not a 38-year-old alcoholic man.

|

The cover painting appears to be modeled on B-movie

actor Sonny Tufts. |

For Lonny, home is wherever his drunken slut of a mother parks their trailer. At the book’s opening, said trailer is parked in a dusty trailer camp in California’s San Joaquin Valley, baking in April sun, turning its interior into an oven. No wonder Lonny gets naked the moment he returns from school. If only his own nakedness didn’t awaken all these confusing urges.

It was crazy to get this way when you took your clothes off. Did it happen to everybody? … Did the rest of it happen, too — the part of you that was supposed to ride quiet and harmless in your pants — did that do this, stretch out, stand hard like this, for other guys? And was there no controlling what you did about it, what your hands did, how your body shouted to be released out of itself, and nothing you could do to stop it?

No sooner has Lonny shot his load than his mother comes home, drunk after having spent her day at “some cheap bar” rather than at work. The mortified teenager waits for the full force of her rage. Instead, she grins and says, “My God, little Lonny’s growing up.”

A couple days later Lonny returns from school to discover Mildred, a friend of his mother’s, waiting for him inside the trailer. Mildred is described as dark (“maybe part Mexican or something”), younger than Lonny’s mother (“maybe somewhere around twenty-five”) and dressed in a halter top and flimsy gingham shorts. Mildred claims she’s just stopped by for a friendly visit, but it’s clear she’s not there to just to chat. After serving Lonny spiked lemonade, Mildred’s undoing the buttons of his Levi’s (“Don’t you know that’s what a woman’s for?”) Only when Mildred is in a post-orgasmic haze is Lonny able to get away “from her [... ] and from his mother, from the men with big cars, from the constant drunks, the early morning escapes, the old Chevy, the dirty trailer, all of it. Forever.”

So begins Lonny’s journey down “Twilight Road.” He’s first taken in by Linus and Martha Brucker, helping the elderly couple on their small farm. The Bruckers are the family Lonny always wished he had, but his happiness is threatened by a visiting nephew, Hal. Though the boys are around the same age, Hal has little interest in being Lonny’s friend — except at night, when he and Lonny are alone in the guest room. But Hal is no queer, as he makes clear the next day. Lonny can suck Hal’s dick (or jerk him off or whatever — the sex isn’t graphically described), but during daylight hours he’d better keep his faggot ass away from him. This doesn’t sit too well with Lonny, though he doesn’t put his foot down until the last night of Hal’s visit. As revenge for being denied a farewell nut, Hal outs Lonny to Uncle Linus, and the old man sends Lonny packing.

He attempts to settle down in another town, taking a job as a dishwasher at a drive-in restaurant, but loses that gig when he refuses to be kept by Mr. Porter, the fat queen who owns the restaurant—and half the other businesses in town. Time for Lonny to hit the road again.

Things improve for Lonny considerably in Lordsburg, where he lands a job as an assistant at the town’s weekly paper, the Standard, owned and edited by handsome, 35-year-old Gene Styles. Lonny throws himself into his work, thankful to have Gene as a mentor and relieved to have such a demanding job to distract him from his homo desires.

An emergency at work returns Lonny’s thoughts to his sexuality. A local judge and the sheriff barge into the Standard office when Gene’s away, demanding an unflattering story about the pair being cruel to out-of-work migrants be pulled (this was over five decades before “being cruel to out-of-work migrants” would be a GOP flex). Lonny calls Gene as soon as the two men leave, surprised when another man answers. The man tells Lonny to come over to Gene’s house, instructing him to come around to the side patio instead of the front door. Lonny does as he’s told, and discovers what most readers will have already guessed:

French doors stood open, and beyond them, inside the room, Lonny saw a rumpled white bed, its blankets fallen to the floor. And on the bed sprawled two naked figures. The back of one was turned, but Lonny recognized Gene Styles. And tangled with his lean, brown arms and legs were paler ones. But not those of any woman, of any wife.

It was a man that was with Gene, another man. What went on? For a crazy instant, Lonny thought it was a fight he saw, a beating, an attempt to choke, to kill. He almost yelled. Then he realized what was happening. His knees went weak. He felt dizzy. He turned and ran.

What I love about the above passage is how Lonny, who, though bit confused about sex, is clearly sexually aware, thinks Gene and his lover are fighting, like he’s an 8-year-old walking in on his parents fucking. (Then again, over half the content on RFC looks like assault to me, so maybe Lonny’s confusion stems from Gene liking it rough.) Lonny’s innocence is further belied when, after getting caught by Gene and assuring the editor he’s not repulsed by his homosexuality and has no intention of quitting, he goes to a diner, cruises a sexy Mexican teen named Pablo and takes him back to his place. Seeing Gene in flagrante-delicto may have made Lonny’s knees go weak, but it also made his cock rock hard.

Anyway, Gene refuses to pull the story, putting him on the sheriff’s and judge’s respective shit lists. But unhappy local officials are nothing compared to his scheming bitch of a boyfriend, Max. Max had set Lonny up to discover the two men fucking in hopes of scaring away Gene’s cute assistant. When that plan backfires, Max just becomes more vicious and pettier.

Though Lonny has assured Gene he’s accepting of the older man’s queerness, he is tight-lipped about his own sexuality — and his relationship with Pablo.When Lonny does finally come out to Gene, the older man’s response is fear that he’s unduly influenced his fair-haired employee (“This is not hero-worship, surely?”) Perhaps most telling of the time this book is written is Gene’s response to Lonny asking if it’s OK to be gay:

“I don’t know,” Styles sighed wearily. “It’s complicated, Lonny. But even if I believed it’s all right, I don’t think I’d tell you. A decent man has obligations, especially to younger men who trust him and look up to him.”

So, in the name of “decency” Lonny must deal with his sexuality in his own way, and secretly. That secret gets out amongst Pablo’s peers, however, and they jump him and stab him several times for being a joto. Pablo’s mother is also aware of her son’s relationship with Lonny and she makes no attempt to hide her contempt when Lonny appears in Pablo’s hospital room. But the sight of his boyfriend brings a smile to Pablo’s face, so of course Pablo’s family and his confessor, Padre Guzman, must do all they can to wipe it off. Pablo, powerless against the relentless Catholic guilt, agrees to move to Mexico, where he’ll finish his education and become a priest.

A heartbroken Lonny later visits Gene Styles at his home. Max has left for the evening — taking all the fuses from the fuse box with him. Once Gene and Lonny restore the power, Gene discovers that Max has gouged deep scratches across all the albums in his collection, rendering them unplayable. Gene’s record collection may be ruined, but the evening isn’t.

Yep, in a turn that’s as surprising as the revelation that Gene’s “family,” the 35-year-old newspaperman and his assistant, now 18, end up spiriting away to a coastal motel for a weekend-long fuck-a-thon. Some might argue that Gene — who has been schooling Lonny on art, literature, and music — has been grooming Lonny all along, but it doesn’t really read that way. Also, Lonny seems to be genuinely in love with Gene (so, fuck off Pablo). They’re more Chris & Don: A Love Story than a SayUncle.com video.

|

It’s easier to accept Gene and Lonny together if you imagine

them looking like a pre-car wreck Montgomery Clift

and a young Tab Hunter. |

But blowing a teenager (presumably) isn’t the worst thing Gene does with his mouth. When Gene isn’t teaching Lonny the many ways to love a man, he’s sharing some more questionable thoughts on what it means to be gay in the early 1960s, such as this tidbit:

“Maybe we always come with the dying of a civilization. I don’t think anybody who took a hard look at the past would tell you differently. When civilizations start to decline, homosexuality not only booms, but gets tolerated.”

He then adds:

“I only know what I like. And I also feel pretty sure you can’t make a crusade out of it, start clubs, wave banners, or lobby for legislation. When tolerance comes, it comes spontaneously. It’s coming now, by the way. Which now I don’t think bodes well for western civilization.”

And finally:

“Being born queer is like being born with any other handicap. You have to make the best of it. But as you get around, you’ll notice a lot of boys and men who seem out to make a show, who wave it in everybody’s face, and then feel hurt when the normal world calls them dirty names. These guys are asking for it—camping it up, flouncing around in drag[.]”

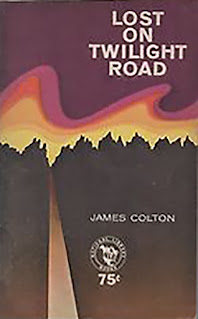

Author Joseph Hansen, in addition to being a trailblazer in gay fiction with his series of mystery novels featuring gay private investigator Dave Brandstetter, helped found the Hollywood Gay Pride Parade, so I don’t think Gene represented Hansen’s views so much as the internalized homophobia of men in his generation. Then again, Hansen was married to a woman for 51 years, so what do I know about his real views?

Mad Max and the Search for El Fumador

Gene and Lonny’s weekend of hot sex is short-lived. When they return to Lordsburg, Gene buys Max off, paying the evil queen a total of $5,000 to get out of his life. Max, however, costs Gene significantly more, tipping off local law enforcement about Gene possessing illicit drugs and pornography, then planting plenty of evidence for the sheriff and his deputies to find when they execute a search warrant on Gene’s house.

Gene is arrested, but, to Lonny’s dismay, doesn’t really try to defend himself during his preliminary hearing (presided over by the same judge featured in the news story Gene refused to pull). It’s better to be convicted on trumped-up drug and pornography charges than reveal the truth about him and Max, whom the prosecuting attorney has already declared “a proven and notorious degenerate. A homosexual.” Worse, the true nature of Gene’s relationship with Lonny could get exposed in open court.

Lonny makes it his mission to prove Gene’s innocence. Max is long gone, so while his daddy boyfriend awaits trial, Lonny goes searching for the only other man who could clear Gene’s name, the ridiculously named El Fumador, a notorious area drug dealer known for his small stature, wearing wide-striped suits, and driving a pink Cadillac. So during the two weeks before Gene goes to trial, Lonny takes the editor’s car and embarks on a search of the San Joaquin Valley for the pink Cadillac.

His search is a failure. At the end of the two weeks Lonny winds up back in the motel suite of Mr. Porter, the predatory queen who propositioned him a year earlier. Broke, defeated, and desperate, Lonny offers himself to Porter, and the hefty homo happily seizes the opportunity (Hansen describes their coupling as a “sad, flabby business”). Yet Porter already has a full-time fluffer, and he’s not about to share his sugar daddy, ordering Lonny to leave or he’ll “cut [his] precious cock off!”

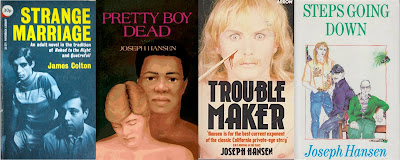

|

Lost on Twilight Road’s

alternate cover design, which

is...better?

|

Just when it looks like Lonny’s story is about to end as it began, with him wandering aimlessly down “Twilight Road,” he spots El Fumador’s pink Cadillac in Lordsburg. He confronts the drug dealing runt, and though he gets El Fumador to admit he planted the pills and porn in Gene’s house, Lonny also gets the shit beaten out of him, then shot at, the bullet grazing his skull. El Fumador runs away as Lonny’s begins slipping toward the downer ending that was required of so many queer pulps.

But not Lost on Twilight Road! Lonny’s skirmish with El Fumador occurred right outside the rectory of the Santa Teresa church, and Padre Guzman, of all people, overhead the whole thing and called the sheriff. El Fumador is arrested, and Gene Styles is released into Lonny’s arms. “I want you whole and with me, now,” Gene says while visiting Lonny in the hospital. “I’ve got so very much to learn from you.”

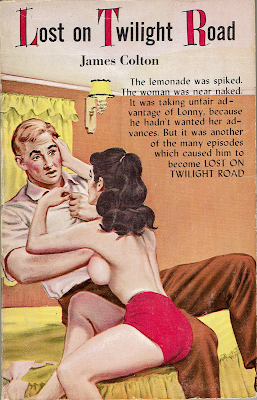

When I first got this book, I expected it to be campy fun. I mean, you saw the cover. How could anyone expect to take this book seriously? Yet Hansen took it seriously when he wrote it under its original title, Valley Boy. (He didn’t care for the publisher’s re-titling, and he described the cover as the “world’s worst cover illustration.” I disagree with him about the publisher’s title, which I find wonderfully lurid, but he’s right about the cover, though I don’t think the boring cover painting of the second edition, which Hansen preferred, was much of an improvement).

|

Bad cover images seem to have plagued Mr. Hansen

throughout his writing career. |

Though there are plenty of moments in the book that make it read like a novelization of a sweaty sexploitation movie, and the name “Lonny Harms” sounds like a character in a John Waters film,

Lost on Twilight Road is more heartfelt than campy. Beneath the titillation of Lonny stumbling from one sexual misadventure to the next is a is an honest exposé of what gay men endure just to get along in the world. Lonny’s transformation from wide-eyed innocent to proud — but not quite out — homosexual may be far-fetched, but it’s also revolutionary for the pre-Stonewall ’60s. Gene Styles’ self-loathing is an unhealthy, hetero-normative way of thinking; Lonny’s self-acceptance is the ideal. Gene Styles is right: he does have so much to learn from his barely legal lover.

Goddamn, this was a long one. (Reader: You’re telling me!) But I really do adore this book, despite its problematic passages. Unfortunately, a more-detailed-than-necessary synopsis might be the closest most readers will get to actually experiencing it. Though Hansen went on to be a successful and acclaimed novelist, his early “James Colton” pulps never got reprinted. I hold out hope that one day these books will find their way into digital markets, like some of Hansen’s mystery novels, but until that day happens, my obsessive review will have to suffice. If that doesn’t get the Hansen estate’s ass in gear to re-release the author’s early pulps, I don’t know what will.