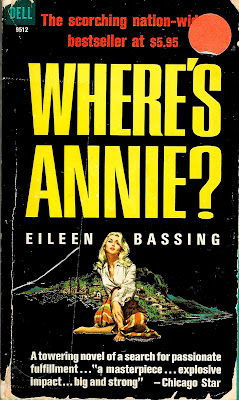

WHERE’S ANNIE? is not just the title of this 1963 novel by Eileen Bassing, it’s also the question I kept asking myself while reading it. Specifically: Where’s Annie, and why is she name-checked in title? Because this novel isn’t really about Annie at all.

Annie, the young trophy wife of a retired navy admiral, is but one of a group of American ex-patriots living in an un-named village in Mexico, and even then she is only a peripheral character, having only slightly more impact on the book’s story as the natives of the village.

The book’s actual main character is Victoria, a middle-aged writer who, after ditching husband No. 4, has settled in the village to write a great novel, provided she can get past her writer’s block. Victoria is not an easy character to love. We first meet her when she nearly collides with Andrew Cunningham, Annie’s unhappy husband, while he’s out for his morning walk. “Out of my way,” she says, as though he’s the one at fault. Victoria is too involved in her own thoughts to waste time with social graces.

Victoria is bitchy, but she’s not heartless. She later comes rushing to Cunningham’s aid when his fishing boat sinks in the lake at the edge of the village, then later she organizes a search for Annie when the admiral’s young bride disappears from a party (insert title drop here).

Annie is ultimately found in the arms of another (younger) man. Annie lamely defends herself, telling Victoria that Cunningham is “so…old.” Victoria encourages Annie to remain faithful to her husband a little longer. “You have time,” Victoria says. “He has…almost no time.” (Bassing is fond of ellipses.)

The Cunninghams leave for the U.S. the next day and Victoria once again focuses on her work. But first, she walks to the post office to see if her agent has sent her a check, then she goes drinking with Charlie, a recovering morphine addict who fights off cravings with booze and pot, and Harry, a junkie who’ll take whatever drug is available. She later meets Ned, a homosexual and gifted artist. Though Ned is perfectly charming, Victoria, who couldn’t give less of a fuck about making a good first impression, is openly hostile. Still, Ned invites her to visit him. She refuses.

Days later she decides to apologize for her rudeness, visiting Ned on the exact same day he comes down with malaria. Victoria elects to stay with him and nurse him back to health, partly out of penance for her earlier treatment of him, but mostly to avoid her typewriter. It’s during this chapter that we get one of the book’s best lines, when Victoria tells Ned, “I’d rather deal with your excrement than your gratitude.”

The pair become friends, but it’s not a healthy friendship. Victoria had to deal with Ned’s literal shit when he was sick but dealing with his metaphorical crap may be worse. It turns out Ned’s charm masks his cold, selfish nature. The pair fight and make-up constantly. He finds her too dowdy, too bohemian, too emotional. She resents his criticisms of her and her writing, but when her temper cools she’s back at his door, seeking his approval. It’s Harry, of all people, who’s the voice of reason:

“[Do] you know what I see Neddy-boy doing? I see him trying to make my Vickie, my original, over into his own mold. He is fashioning, as though he were God, another little Neddy-boy.”

Harry is a drug addict and shit-stirrer, so Victoria dismisses his observations. Besides, she’s too preoccupied with what Ned’s cat is thinking to pay attention to what Harry says.

Let me explain: Late in the book Ned gives Victoria his cat, Hassan, to care for while he’s out of town. This cat behaves like most cats (lies there, mostly), much to the consternation of Victoria.

Could it think? She stared at it and the cat stared back at her, in cross-eyed indifference. After a moment — and she was aware that a lot of time passed this way, hypnotically, with her staring at the cat and the cat staring back at her — it reached out with its paw and pushed at an envelope which was on the shelf near it. The cat did not watch the envelope flutter to the floor, as she did. But wasn’t that proof, since it was a deliberate act, that the cat must have some thought, some reasoning process? Then what could its reasoning process be?

The above text is but a mere taste of Victoria’s obsessing over this cat. Bassing devotes almost

three fucking pages to Victoria wondering what makes this goddamned cat tick. I only bothered with one of those pages.

And this tangent about the mysteries of cat thought highlights my biggest problem with

Where’s Annie? For all the well-drawn characters and sharp observations, Bassing too often gets bogged down in minutiae at the expense of the story’s momentum. This is a loose, character-driven narrative, with as much attention given to the characters’ inner lives as to the story’s minimal action, but I would argue that any inner life that dwells on the inscrutability of cats is perhaps not a life not worth reading about.

Not helping is Bassing’s tendency to try too hard, her writing often self-consciously literary, as if she’s more interested in impressing critics than engaging readers, similar to how Victoria tailors her writing to please Ned rather than herself. Consequently, this book felt longer than its 382-pages.

But

Where’s Annie? has a lot to recommend it. Victoria isn’t particularly likable, but she is relatable. I’ve known people like her—I’ve been friends with them—and as in real life, I was alternately drawn to Victoria for her acerbic wit and put off by her surly attitude. Still, even though I didn’t entirely like her, I didn’t think she deserved the treatment she got form Ned.

Speaking of Ned, while I wouldn’t nominate Bassing for a GLAAD award, her treatment of Ned’s homosexuality is pretty progressive for 1963. She matter-of-factly acknowledges Ned’s queerness (Ned has a boy toy, Manuel), but his homosexuality never becomes his sole character trait. In fact, there are only a couple instances in the book when characters make derogatory comments about Ned’s sexuality. People don’t dislike him because he’s gay, they dislike him because he’s an asshole.

I didn’t know anything about Eileen Bassing when I was given this book five years ago (my nephew saw it at a used bookstore and thought it looked like something I’d read). Besides

Where’s Annie?, she wrote the novel

Home Before Dark. According to her

obituary — she died in 1977 at age 58 — she also was a screenwriter (she adapted

Home Before Dark into a 1958 movie starring Jean Simmons), a story editor and an advisor for the motion picture and TV industries. I’ve seen

Home Before Dark and recommend checking it out next time it appears on the TCM schedule.

Where’s Annie? is worth checking out, too. If you can fight the temptation to abandon the search early,

Where’s Annie? is ultimately a satisfying read.