When I first teased this eventual review, I referred to Buried Blossoms as a “Flowers in the Attic knock-off,” an observation I based solely on the book’s cover. There are some similarities between Blossoms and V.C. Andrews’ mega-hit Flowers—a wealthy, fucked-up family, children living in isolation, incest—but it’s not a direct rip-off. In Blossoms, the children of the wealthy Hazeltine family aren’t the victims of evil adults but rather corrupted by their domineering father, who uses his money to isolate himself and his family from the New England town in which they live.

That town is Eastfield, Massachusetts, the founding of which we learn far more than is necessary to the story. All you really need to know is the town has planned a bicentennial celebration July 4, 1896, and Paul Hazeltine, owner of the Hazeltine Buggy Works, the town’s largest employer and responsible for Eastfield’s current notoriety and prosperity, has been tapped to be the event’s keynote speaker.

His acceptance of the gig is something of a surprise as Paul Hazeltine has made it abundantly clear that he gives not one shit about the silly residents of Eastfield. He keeps his family sequestered in a palatial estate outside the city limits, his beautiful, compliant wife Olivia, and their children only venturing into town for infrequent shopping trips. The kids don’t even attend school, Paul Hazeltine insisting that they be home schooled instead, not for religious reasons (he’s a staunch atheist) but because he doesn’t want his children mingling with the lowly town folk.

His son, Paul, Jr., buys into the belief that their family is superior. When he’s taunted by one of the local boys during one of those rare shopping trips, Paul, Jr., calmly tells him to stop.

“Why?” the boy who

started [sic] teased. “What are you gonna do about it? Fight?”

Paul Hazeltine,

Jr., shook his head. Instead of the reaction his tormentor had expected, his

face was set in a superior smile.

“What then?”

“I’m going to tell

my father,” Paul said. “And then your father won’t have a job. And you won’t

have any food. And you’ll die.”

Unlike her brother,

the oldest Hazeltine daughter Francine isn’t interested in being superior to other

kids, she wants to be one of them, to have friends (she wants a friend so badly

she later invents an imaginary one). Her mother wants the same thing, and even summons

the courage to ask her husband if they could, perhaps, host a party at their

house. His response is immediate and harsh: “Certainly not!” Olivia demurs,

because it’s 1896.

The day of the bicentennial arrives, and the Hazeltines make their grand entrance driving to the event in an electric car developed at the Buggy Works. Paul Hazeltine touts it as a sign of things to come. Electricity, he tells the crowd, will power carriages and power homes. This being a time before people worshiped the rich and took their word as gospel, the crowd is skeptical, some of them mocking Paul Hazeltine for suggesting such a ridiculous idea. Eventually, he wins residents over, selling them on the idea that Eastfield, currently benefitting from the success of Hazeltine Buggy Works, will soon grow exponentially when the Hazeltine Electric Car carries them into the 20th century.

The novel doesn’t really get hopping until it jumps to 1903. Olivia’s fifth child (besides Paul, Jr., and Francine, there’s Margaret and Constance, the youngest) is stillborn, and so deformed it’s barely recognizable as human (Its mouth and nose were one. There were gill-like slits at its throat and rigid flaps of skin where its arms and feet might have been.) The Hazeltine Electric Car has stalled and died, losing out to gas-powered cars. Rather than live with his failure, Paul Hazeltine, locked alone in his study, kills himself by drinking ink, of all things.

It's Olivia, deciding to surprise her husband with a midnight visit to his study, who discovers his body and promptly loses her mind. Refusing to admit the reality of his death, Olivia tosses Paul’s suicide note into the fire and then drags her husband’s corpse out of the house, which sort of strains credulity. Olivia is described as having a slender build and, at this point in the story, has a growing dependence on morphine. It seems unlikely she could drag her husband’s dead ass through the house by herself without drawing the attention of one of her children or their maid, Brigid. But no one ever hears her, and so Olivia drags Paul’s body out to the ice house and buries him there.

No one hears Olivia as she disposes of Paul’s body, but her teenaged children Paul, Jr., and Francine see her from their bedroom windows. Her children don’t confront her the next morning, though, even when Olivia announces that their father has been called away on business. “But we have a man of the house all the same,” she tells her children, referring to her son. Paul, Jr., the little fucker, immediately embraces his new role, asking if he could take his father’s place at the head of the table until his father returns, knowing he never will. Olivia agrees, before drinking a glass of morphine-spiked water, because ladies don’t mainline.

|

| Jove Books gave Buried Blossoms a snazzy keyhole cover |

Incest, Madness and Murder

Paul Hazeltine was cold

and domineering. His son, on the other hand, is a little psychopath. He

overhears Francine telling her imaginary friend Jane that Olivia is mad and

confronts her, slapping her and pinning her to the floor.

Paul’s hand covered

her mouth, then his face pressed against hers and his hands were all over her

at once, along her legs, under her dress.

When she tried to

pull away, he pinched her, butting his head against her face. He forced his

hand between her legs, laughing to himself as she shook with terror. Then, as

suddenly as it had begun, the attack was over.

“I’m the man of the

house now,” Paul told her, standing up, smiling, leaving.

|

| Buried Blossoms is better edited than the typo-riddled Love Merchants, but a copyeditor clearly lost his/her place when copying and pasting sentences in this paragraph. |

The maid is horrified further when Paul takes a cross from his pocket—a cross that Brigid had given Francine earlier—and slips “the chain over his penis, so that the cross dangled from it.”

Brigid flees the bathroom, intending to flee with the girls, but making no effort to get them away from their brother at that very moment. Paul, Jr., doesn’t remain in the bathroom, instead following Brigid, taunting her with his cross-festooned dong. Were it not for what transpired immediately prior, the mental picture of Brigid fleeing in terror from a teenager brandishing his hard-on is kind of funny. The laughter ends when Brigid is at the top of the stairs and Paul throws the crucifix at her, sending a startled Brigid tumbling down to the first floor, and to her death.

Francine realizes escape is necessary if she’s the avoid the fates of Brigid or her mother, who is now floating through her days zombified on morphine and wine. During a trip to town to collect the family’s mail from the post office, she’s offered a ride from a young traveling salesman named Ned. Ned’s motives are sus, but Francine doesn’t give a shit. Not only is the salesman cute, but he’s also a potential savior. So what if it takes a blowjob and a quick fuck to convince him to take him with her?

One of the bigger surprises in Buried Blossoms is that Francine’s planned escape with Ned goes off without a hitch. I really expected Ned not to show up to their planned meeting at the train station, or for Paul to stop her from keeping the date, but Ned does, and Paul doesn’t. Ned does ditch her not long after (I knew he was a piece of shit), but Francine doesn’t care. She’s out of Eastfield and away from her fucked-up family.

While it’s great

that Francine got away from her horrible life in Eastfield, we’re only at the

novel’s midpoint, making it a little soon to dismiss her awful family from the

story. Lewis or whoever (see below), evidently realized this, as he returns Francine to Eastfield 20

years later.

In those 20 years,

Francine became an actress. Known as Francine Le Faye, she travels the country in

touring productions of Broadway plays, which is how she ends up in Eastfield.

She’s understandably nervous about being there—she has, in the past, turned down

roles in plays that would take her in the vicinity of her family home—but she’s

also curious about what’s happened to her family, her mother and sisters especially.

So, against her better judgment, she pays them a visit.

She’s alarmed to discover that the Hazeltine estate has fallen into disrepair, its once-cultivated gardens overgrown with weeds, the house itself overgrown with vines. Margaret and Constance answer the door, and though they are grown women they act like little girls, and they behave as if they’re members of a religious cult. Their answers to her questions are cryptic: their mother has “gone away”; their brother is “the same.” Creepy as they are, visiting with her sisters is reasonably pleasant. That changes when her brother. enters the room.

But Paul, Jr., coldly indulges Francine’s visit, giving equally evasive answers to her questions about their mother. Margaret and Constance then give her a cup of tea. “You wanted something of Mother’s,” Paul said. “So now you have her favorite. Her medicine.”

Francine’s visit becomes imprisonment, during which her brother and sisters cut off all her hair and repeatedly sexually assault her. It should be mentioned here that although Lewis’ writing career was primarily made up of porny “exposés” about prostitution (Massage Parlor; Teenage Hookers; Housewife Hookers) and novels about the sexploits of the rich and famous (The Best Sellers; Expensive Pleasures), and the 1980s still being a time when the marketplace rewarded graphic descriptions of sex, no matter how repugnant the circumstances, the descriptions of sex acts in Buried Blossoms are relatively restrained. In fact, Lewis adopts an almost stream-of-consciousness style as Francine struggles to make sense of what’s happening to her, thinking it’s a dream.

It’s not a dream, but it’s not a nightmare from which she’ll wake up anytime soon, even after she escapes, burned, battered, bald, and batshit. For the rest of the book, Francine will remain hospitalized, in a catatonic state and unable to tell the investigators her name, let alone what happened to her.

The remainder of the book concentrates on Paul, Jr., Margaret and Constance, detailing their lives in the early1940s as an incestuous throuple, Paul, Jr. hunting game (and killing a kid who dared knock on their door), Margaret cooking their meals with assistance from Constance. Rather than any great dénouement, however, they merely get old and die, one by one.

Was Blossoms Ghostwritten? Let’s Speculate!

Buried Blossoms was not Lewis’

first foray into the horror genre, at least judging by titles in his

bibliography. He previously published Something in the Blood and Natural

Victims, though I couldn’t even find a cover of either online, let alone synopses,

so their being horror novels is an assumption on my part.

|

| Stephen Lewis’ author photo from the back of his 1973 book, Sex Among the Singles. |

So, given Lewis’ history of writing sleaze and not putting much effort into doing so, I really had my doubts he’d be as adept at writing horror, yet Buried Blossoms is actually pretty effective. It’s superior in many ways to the other Lewis novel I’ve read, The Love Merchants. As much as I enjoyed The Love Merchants, I could fully believe that it was cranked out while he kept one eye on his game shows. But Buried Blossoms reads like it was written with a bit more care, like Lewis was interested in doing more than just getting paid and left the TV off. However, Blossoms was published a year after his death, with the copyright belonging to a George Kuharsky. At first, I naively thought Kuharsky was a family member or partner who inherited Lewis’ unpublished manuscript, but I'm now more inclined to believe he was a ghostwriter hired to complete Lewis’ unfinished book.

Adding credence to

that ghostwriter suspicion is the uneven quality of Blossoms, which

never adds up to a satisfying whole (mitigating factor: The Love Merchants wasn’t

exactly a fully satisfying read, either). It either needed to be a lurid family

saga told in 400-plus pages, or a more concise gothic horror, told in under 200.

Instead, it’s a meandering 297 pages, not really getting to the creepy stuff until

nearly 80 pages in. I’d be tempted to blame this on Lewis trying to reach a

specific page count, except some of the chapters seem a little too fussy,

like the five pages detailing Eastfield’s founding, which beyond being four

more pages than Lewis would ordinarily supply, seems to also include way more

historical research of Massachusetts history than I’d expect from an author

more inclined to detail the sexual adventures of hookers while he watched The Price is Right. But, who knows, maybe

Lewis took an interest U.S. history before dying in his early 30s.

Despite its uneven

storyline, and regardless of who finished it, Buried Blossoms is worth

checking out, and usually pretty easy to find for sale online, at affordable

prices, too. Reading it made me tempted to check out one of Lewis’ other (presumed)

horror novels, which are also for sale online. However, I’m more tempted to

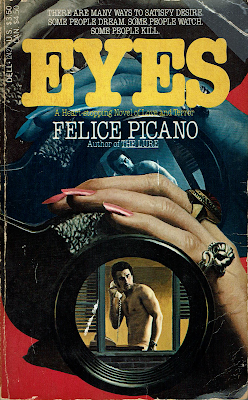

read and review his other posthumously published novel from the gay publishing house Alyson:

|

| Stephen Lewis’ last (?) published novel. |